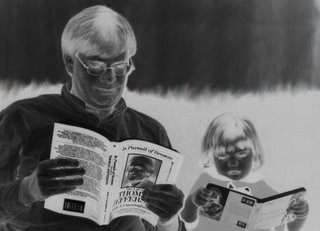

Summary of book

The Democratic Party has changed. More often than not, it loses national elections, and we have seen the erosion of important parts of its base. Taylor looks beyond the shortcomings of individual candidates to focus on the party’s real problem: Its philosophical underpinnings have changed in ways that turn off many Americans. The thought and careers of William Jennings Bryan and Hubert Humphrey are used as case studies to examine this change and its institutionalization under FDR is explained.

How democratic, really, is the Democratic Party? Presidential contenders still make the rounds of Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners, but how faithful has the party been to its founders and their principles? While many rank-and-file Democrats still hold to traditional views, that’s not the case with those who finance, manage, and exemplify the party at the national level. They have adopted an ideology that is inherently unpopular. Turning their back on the thought of Thomas Jefferson, the party has embraced the views of his arch-rival, Alexander Hamilton.

Democrats won the 2006 midterm election not because they were popular but because Republicans were even more unpopular. The rock-bottom public approval rating of Congress in 2008 was confirmation. New members of Congress of a more populist and libertarian stripe, including Jim Webb of Virginia and Jon Tester of Montana, were exceptions to the rule. The 2008 and 2012 victories of Barack Obama were part of the same story. Far from being harbingers of a new sustainable majority, they were more Republican losses than Democratic victories. In a two-party system, voting for a Democrat is the only way to punish a Republican.

If national party leaders are committed to elitist ideas--some as old as eighteenth-century conservatism and some as modern as limousine liberalism and political correctness--is it likely Democrats will regain majority status on a consistent basis? What changed and why?

BOOK REVIEWS: http://www.wheregorev.blogspot.com/

<< Home